The Physiology Of The Large Intestine

Stool moves through the intestines with mixing and propelling movements. During this process the absorption and secretion of substances takes place.

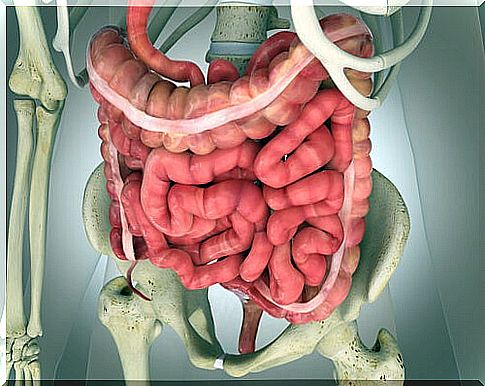

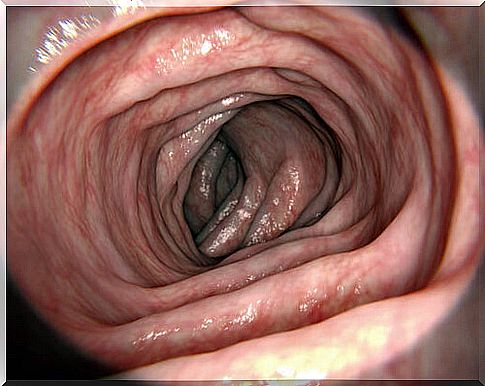

Before proceeding to the presentation of what constitutes the physiology of the large intestine, it is necessary to remember that we are referring here specifically to the final section of the digestive tract.

It consists of the following parts: cecum, colon, rectum and anal canal. In short, they are the widest and shortest part of the digestive tract.

The function of the large intestine is the absorption of water and electrolytes, on the one hand, which is carried out by the nearest half. And on the other hand, the storage of fecal matter until its expulsion, which is carried out by the more distant half.

These functions do not require the peristaltic movements performed by the colon to be as intense as in the previous sections. In fact, they are slow and gentle (“ lazy ”). Despite this, colon movements have similar characteristics to those of the small intestine.

Peristalsis

This term of peristalsis is used to designate all of the contraction movements of the digestive tract. It allows the movement of fecal matter towards the anus. In other words, these are the bowel propulsive movements.

Physiology of the large intestine: colon movements

As in the small intestine, colon movements can also be divided into mixing and pushing movements.

- The mixing movements are explained by the combined contraction of the circular and also longitudinal muscles of the colon. This causes the unstimulated part of the colon to protrude outward in the form of bumps called “bumps”.

A few minutes later, the process is repeated at a nearby location. So that the fecal matter moves forward as if we were “milking” the large intestine. In this way, all the feces are exposed to the intestinal wall, thus facilitating the electrolyte absorption.

- Propulsive movements depend on “mass movements”. This is a type of modified peristalsis that causes a segment of the colon to act as a single unit. And pushes the fecal matter forward.

These movements occur 3 times a day and last about 30 minutes each time.

How do these movements begin?

Mass movements occur in response to bloating of the stomach and duodenum (gastrocolic reflex and duodenocolic reflex). Other times in response to irritation, as is the case in patients with ulcerative colitis.

Role of the ileocecal valve

The ileocecal valve prevents stool from returning to the ileum once it has reached the colon. This is because the degree of contraction of the ileus-calcareous sphincter and the peristalsis of the ileum are subject to reflexes from the cecum.

When the wall of the cecum is distended, signals are emitted which increase the contraction of the sphincter and inhibit intestinal peristalsis.

What happens when processes are corrupted?

In a general way :

- Excessive intestinal motility leads to decreased absorption of substances and the appearance of diarrhea or loose stools.

- A defect in intestinal motility leads to increased absorption of substances and the appearance of hard stools. They are responsible for constipation.

Physiology of the large intestine: defecation reflexes

The expulsion of stool is due to bowel reflexes of defecation:

- The intrinsic reflex, transmitted by the enteric nervous system of the rectum (in itself too weak)

- The parasympathetic reflex, carried by the fibers of the pelvic nerves and which also acts as a reinforcement

How does it happen ?

The arrival of stool to the rectum causes tension on its wall, which sends afferent signals through the myenteric plexus. In response to this, peristaltic waves are triggered from the colon to the rectum and push stool into the anus.

The myenteric plexus emits inhibitory signals that relax the internal anal sphincter. So that when the peristaltic wave reaches the anus, the stool continues to advance. The relaxation of the external anal sphincter is done consciously.

On the other hand, when the nerve fibers in the anus are stimulated, afferent signals are sent to the spinal cord. These return through the parasympathetic nerve fibers of the pelvic nerves. They stimulate peristalsis and also help relax the internal anal sphincter.

Physiology of the large intestine: secretion of substances

What substances are secreted?

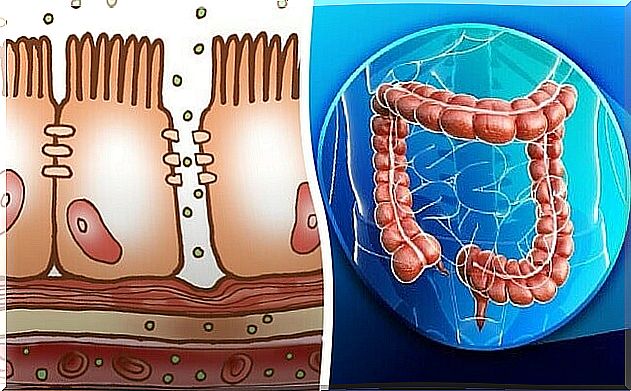

In the large intestine, only mucus containing moderate amounts of bicarbonate ions (pH> 8) is secreted.

The secretion of this mucus is provided by the mucous cells of the intestinal wall and the mucous cells found in the Lieberkühn crypts (simple tubular glands of the small intestine).

Bicarbonate secretion is also produced by epithelial cells other than the mucous membranes and is responsible for the alkaline pH of the mucus.

How is it produced?

The secretion of mucus is mainly triggered by direct stimulation of the mucous cells. So that it increases in response to stimulation of the pelvic nerves (parasympathetic innervation).

What is his goal ?

The secreted mucus has three functions:

- First of all protects the intestinal wall against possible abrasions and faecal acids (the pH of the mucus is> 8 by bicarbonate ions).

- Keeps stools compact.

- Also protects the intestine from bacterial activity.

Physiology of the large intestine: absorption of substances

About 1500 ml of stool passes through the large intestine every day. Most of the water and also of the electrolytes it contains are absorbed mainly in the proximal half of the colon. So the expelled stool contains only about 100 mL of water and between 1 and 5 mEq of sodium and chlorine ions.

How are substances absorbed?

Sodium is absorbed by active transport by means of the Na-H exchanger. Thanks to the resulting gradient of positive charges, part of the chlorine ions are passively entrained in the cells. The remaining chlorine ions are absorbed by exchange with bicarbonate ions.

Potassium as well as other ions like calcium or magnesium are also absorbed in the intestine by active transport.

The joints between cells in the large intestine are also much narrower than in other parts of the digestive tract. This prevents retrograde diffusion of ions and also allows much more complete absorption of sodium.